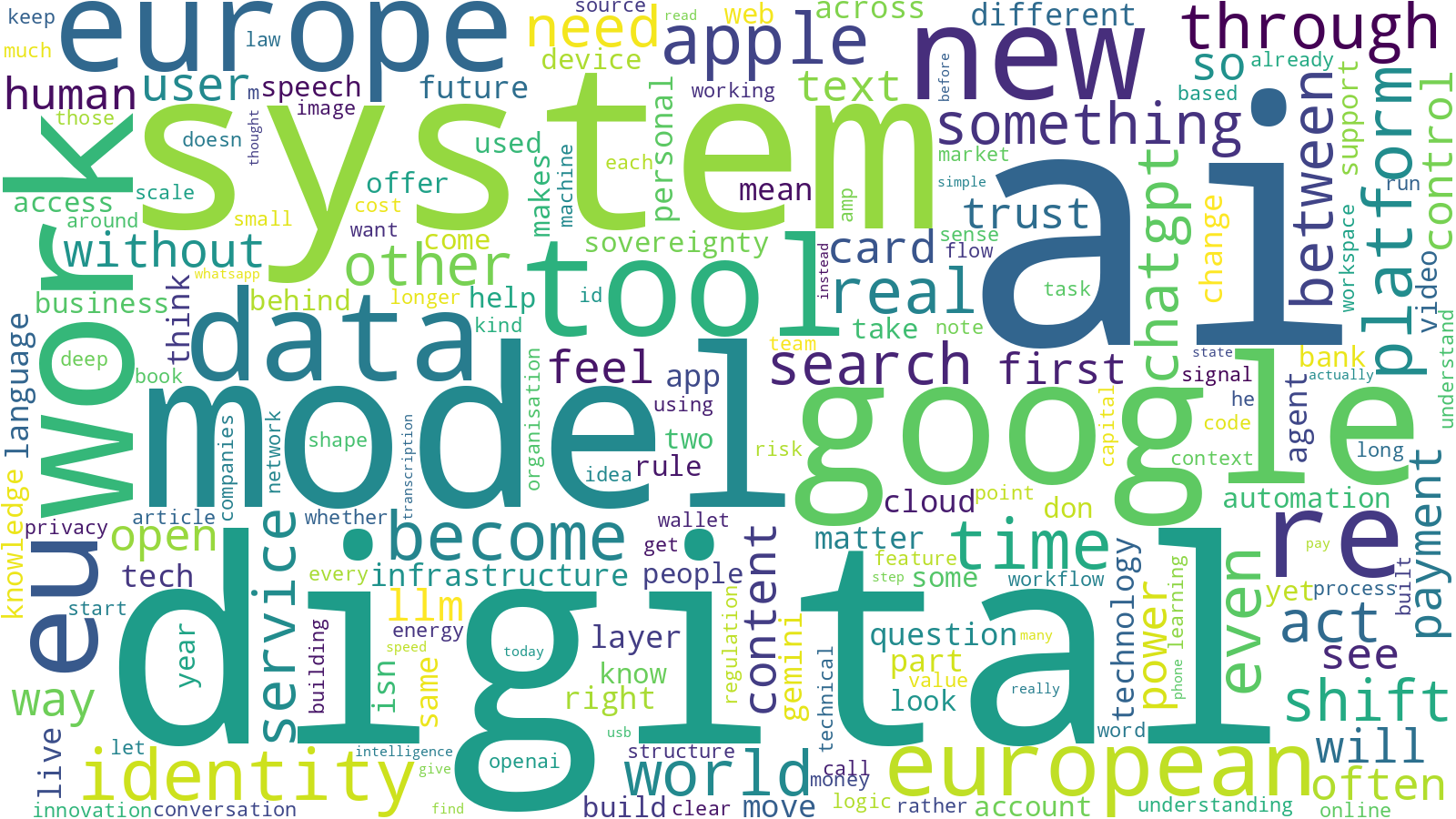

Word of the year: model

The word model comes from modulus, Latin for ‘measure’. It refers to simplified representations we use to make sense of reality, from maps to AI systems.

When I looked back at the words that kept appearing in my work this year, one stood out more than I expected: model.

Not because it felt central or dramatic, but because it was everywhere. In AI, obviously. In strategy documents. In conversations about organisations, processes, responsibility. Even in fairly ordinary moments. The word kept resurfacing, quietly doing work.

At some point I realised I was using it constantly without really stopping to think what I meant by it. And the more I tried to pin it down, the more elusive it became. Not vague, but flexible. Almost suspiciously so.

This piece is an attempt to understand that flexibility. Not to define model, but to ask: how did we get here, and why does this word fit so many domains so well?

The everyday meanings we hardly notice

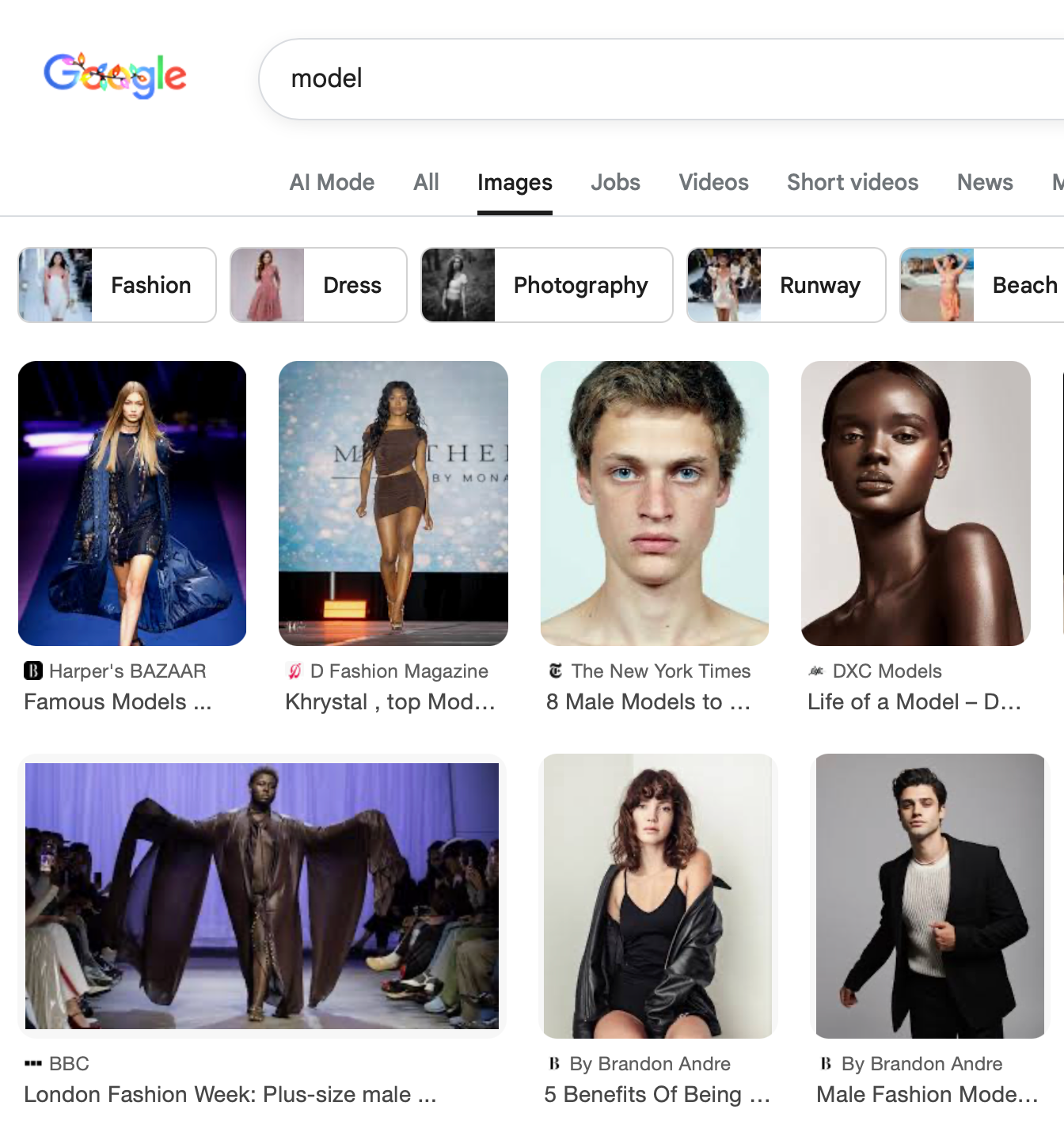

If you search for model, you will likely land on fashion models first. Photo models. People.

That might seem like a distraction, but it is actually a useful starting point. A model here is an example. Something you look at in order to orient yourself. This is what it looks like. This is what it could be.

We use the word like this all the time.

A role model.

A model student.

A model answer.

In all these cases, the model is not a description of reality, but a reference point. It reduces complexity by embodiment. Instead of rules or explanations, you get an instance you can copy, approximate, or respond to.

Alongside this, there is another everyday sense that feels more abstract.

Scale models. Maps. Diagrams. Calendars. Dashboards.

These are not things you imitate, but things you use to navigate. They deliberately leave things out so you can act. A map is not the territory, but it is still indispensable.

Already, the word is doing two different jobs: showing what something looks like, and helping you move through complexity.

That tension turns out to be important.

A small detour into etymology

The word model comes from the Latin modulus, a diminutive of modus.

Modus means measure, manner, way, method. Not an object, but a way of doing something. A pattern that makes action possible.

Modulus is a small measure. A manageable unit.

This matters more than it might seem. From the start, a model was not meant to be the world in miniature, but a chosen scale. A way of handling something too large, too complex, or too messy to grasp directly.

A model is already an admission: we cannot deal with everything at once.

That quietly underpins almost every use of the word today.

Two paths that never really split

Historically, model developed along two closely related paths.

On the one hand, the model as exemplar.

A sculpture model. A pose. A prototype. Something you look at and emulate.

On the other hand, the model as representation.

A plan, a sketch, a proportional guide. Something that captures relationships rather than appearance.

These were never cleanly separated. A sculptor’s model was both something you looked at and something you built from. It guided action without claiming to be the final thing.

That dual role has always been there. The confusion around model today is not new. It is inherited.

From craft to science

When science and mathematics adopted the word, they did not change its meaning so much as tighten it.

A mathematical model is a reduction of reality, expressed in symbols, designed to preserve certain relationships while ignoring others. An economic model does the same with incentives, behaviour, and constraints.

These models are explicit about what they leave out. They are tools for thinking, not claims to completeness.

This is why scientific models are always accompanied by assumptions, boundaries, and caveats. Not because they are weak, but because their strength lies precisely in being limited.

They help you see a system. They do not pretend to be it.

When models start to build things

Engineering shifts the balance.

Here, models are no longer only aids to understanding. They become instruments of construction.

A blueprint is a model.

A data schema is a model.

A software architecture is a model.

Change the model, and you change the system.

At this point, the model stops being merely epistemic and becomes operative. Errors are no longer just misleading. They propagate.

This is where the stakes rise, and where the word model starts carrying real authority. Not because it is more accurate, but because it has consequences.

Language models sit on the fault line

This long history helps explain why model feels so overloaded in AI.

A language model brings all these meanings together.

- It is a statistical reduction of language, trained rather than reasoned into existence.

- It produces exemplars: plausible sentences, answers, styles.

- It is deployed as an operational system.

- And it is used by people as a way to explore, understand, and make sense of domains.

It is, at the same time: something that generates behaviour, and something we use to think with.

This collapses an old distinction between models that help us see systems and models that are systems. No wonder the word feels unstable here. It is being asked to do everything at once.

Much of the current confusion around AI is not technical, but semantic. We slide between treating the model as a tool for exploration and treating it as an authority. Between using it as a map and mistaking it for the territory.

The word model quietly enables that slide.

Why this word keeps appearing

Looking back, I think this explains why model surfaced so often for me this year.

It is a word that allows us to work with complexity without fully resolving it. It lets us act, decide, and build while acknowledging that what we are doing is partial and provisional.

At the same time, it carries a risk. A model can easily stop being a choice and start feeling like reality. Especially once it is embedded in systems, dashboards, policies, or software.

The problem is rarely the model itself. It is forgetting that it is a model.

Seen this way, model is not just a technical term, but a cultural one. It sits at the boundary between understanding and authority, between representation and action.

That is probably why it is almost everywhere now. And why it is worth pausing over, at least once, to ask what we are really doing when we invoke it.

Not to pin the word down, but to keep it honest.