What coding with AI feels like now

There is a lot of noise about AI replacing programmers. I wanted something else: a sense of what is feasible, what is throwaway, and where judgement still matters.

Notes from the edge of building with LLMs

I am all in on large language models as cognitive amplifiers. I use them to think, to structure, to explore, to write. That part feels natural to me. What I have never been particularly drawn to is using them as coding tools. Programming has always felt like a different craft. Adjacent, interesting, but not where I naturally place my attention.

And yet, over the past months, that boundary has become harder to ignore. Not because I suddenly wanted to become a developer, but because clients started asking different questions. They see headlines about “AI eating code”. They see demos racing past on LinkedIn. And they wonder whether they are missing something important.

So I decided to explore. Not to reskill, but to orient myself. To understand what is actually changing, where agency now sits, and what is realistically accessible to people who are curious, but not intent on becoming software engineers.

What follows is not a survey. It is a short field note, guided by my own steps.

Standing near the edge of coding

I have never really been a coder. I know enough to follow along, to collaborate, to get something running from GitHub if I have to, but it has always felt like a different craft. Interesting, sometimes impressive, but not where I naturally operate. You may recognise that position. Curious, not allergic to technology, but not inclined to disappear into documentation or frameworks either.

What surprised me in these experiments was not how powerful the tools were, but how quietly the boundary shifted. Not because I learned a new skill, but because the effort moved. An idea could turn into something that actually works. Not a mock-up, not a diagram, but a usable thing.

That was new to me. Not spectacular, but disorienting in a subtle way.

First encounter: describing a thing into existence

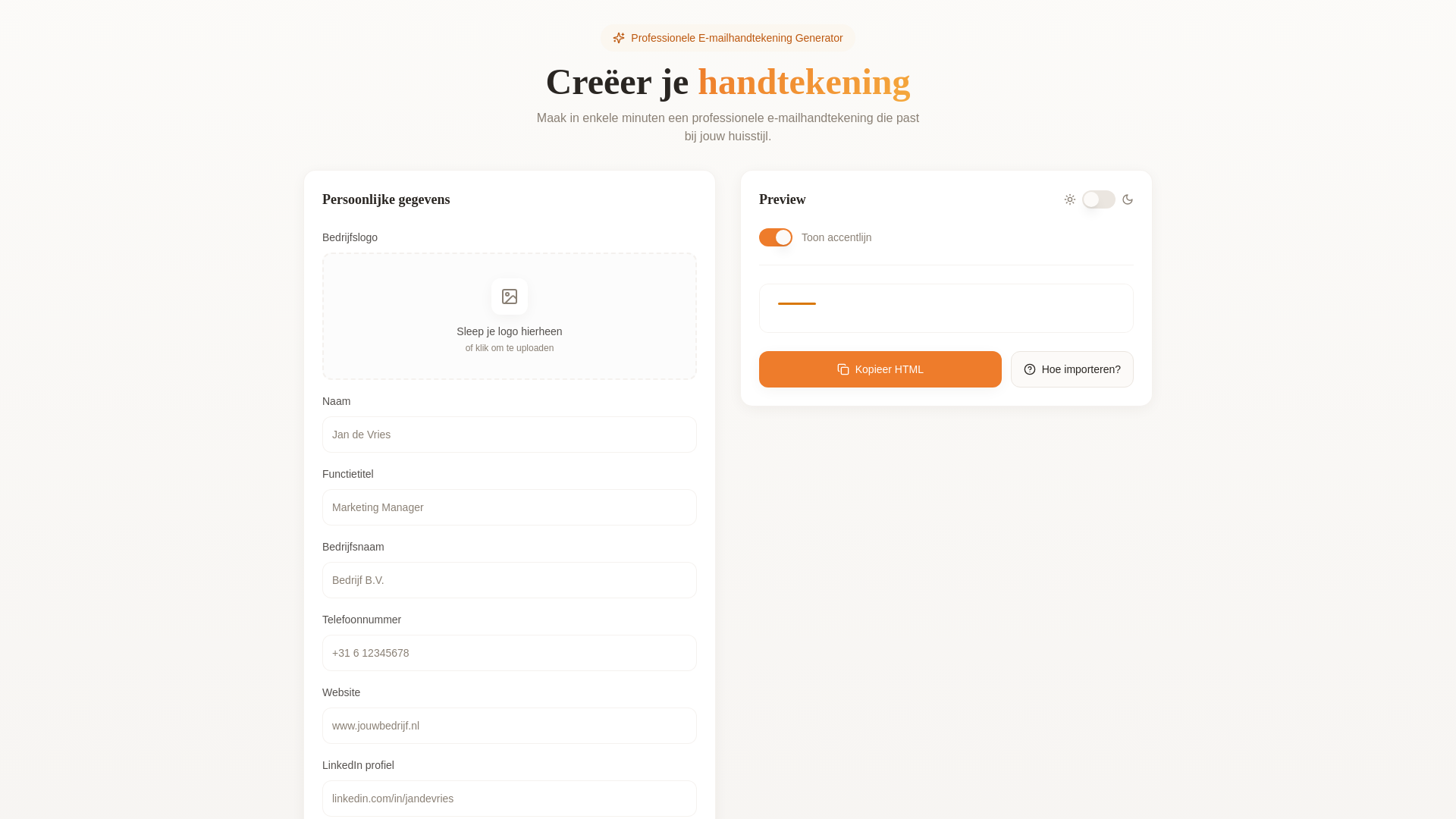

The first thing I tried was Lovable.

Someone shared a prompt for building a simple email signature generator. I copied it, adjusted it slightly, and watched the result appear. A working interface. Inputs, preview, export. No setup, no explicit architectural decisions on my side.

What struck me was how familiar this felt. This was not programming in the traditional sense. It felt much closer to product definition. Describing behaviour, constraints, and outcomes. The kind of thinking that normally stops at wireframes or tickets.

Here, the description executed.

That is the strength of tools like this. They let you stay at the level of intent and outcome. At the same time, the trade-off is clear. Many decisions are made for you. Hosting, structure, deployment, all of that is implicit. You gain speed and clarity, but give up control.

For an experiment, that was exactly right.

A step deeper: intent meets a project

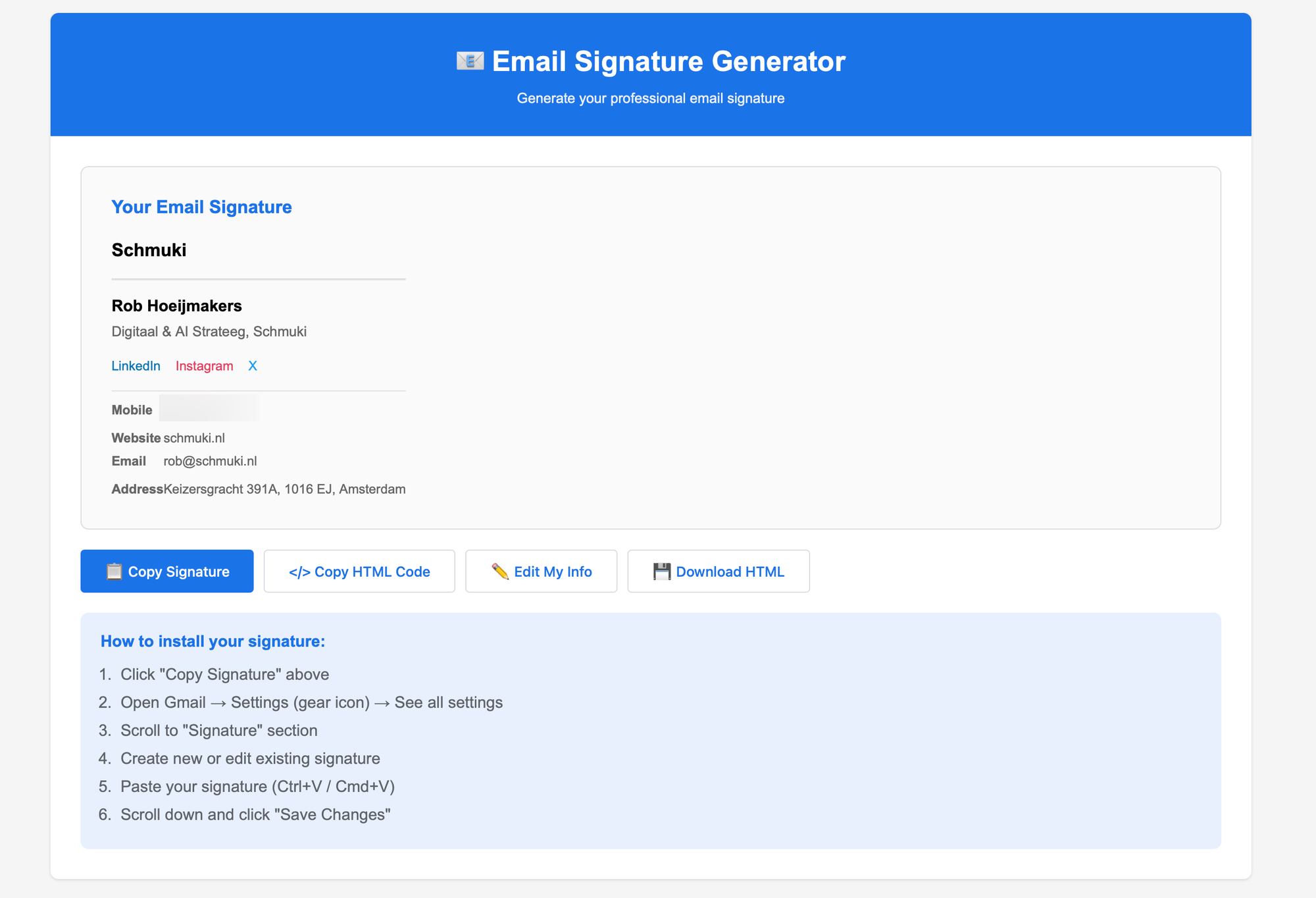

Curiosity pulled me one layer down. I wanted to see what would happen if I stayed close to intent, but entered a recognisable software project.

I tried Claude Code and connected it to GitHub. This time, the result was not an abstract app, but a repository. Files, versions, commits. I used it to build a bespoke email signature generator inside Google Workspace, backed by a Google Sheet and implemented with Google Apps Script.

The experience changed in kind.

Claude Code did not “build an app for me”. It helped me think through a project. What goes where. What changes when I adjust something. How to iterate, deploy, and improve. The LLM was no longer replacing structure. It was inhabiting it with me.

I also felt a boundary. Systematic software development, long-term maintenance, deeper architectural decisions, that still felt like a different craft. Not inaccessible, but distinct.

What mattered was that this boundary was now visible.

What people mean when they say “IDE”

This is where the term “IDE” often comes in. IDE stands for Integrated Development Environment, but that label tends to obscure more than it explains.

In practice, an IDE is the place where software lives while it is being made and maintained. It is where files are organised, changes are tracked, versions are compared, and decisions accumulate over time. Not just a text editor, but a working environment with memory.

A widely known example is Visual Studio Code, used by many developers and familiar to a broader technical audience. What is changing now is not the existence of such environments, but their role.

With LLMs embedded, IDEs start to absorb more of the thinking, explanation, and iteration that used to happen outside them. They begin to look less like specialist tools and more like shared workspaces between human and system.

Three ways of building, loosely speaking

Looking back, what helped me make sense of this was not taxonomy for its own sake, but orientation. Roughly speaking, I now see three modes people move between.

First, outcome-driven tools like Lovable, where you stay at the level of intent and receive a working artefact.

Second, artifact-centric assistance, where LLMs help you produce scripts, components, or configurations that you then integrate yourself.

Third, IDE-centred environments, where the LLM is embedded into the development workflow itself and develops a persistent understanding of a system over time. Tools such as Cursor are often mentioned in this context, as are Codex-based systems from OpenAI.

These are not strict categories. They overlap and evolve. But they differ in one crucial respect: where your agency sits. At intent. At artefacts. Or at systems.

What has changed is that moving between these layers no longer requires a hard identity shift.

A signal worth paying attention to

This is also why it is telling to see Google presenting tools like Antigravity explicitly as a “next-generation IDE”. Even if such tools are still emerging, the framing itself matters.

It suggests that IDEs are no longer seen only as specialist developer tools, but as environments where complex work takes shape, especially when that work results in living systems rather than finished documents.

That matters even if you never plan to work there yourself.

Abundance, noise, and judgement

One effect of this shift deserves a little more attention. As software becomes easier to create and easier to discard, the market around it changes shape.

We move away from a relatively structured landscape, with high entry costs and clear thresholds, towards something more crowded and informal. A place with many small offerings, many claims, many tools competing for attention. At times, it starts to resemble a medina: lively, inventive, and full of possibility, but also noisy and disorienting.

In such an environment, the hard part is no longer building something. The hard part is knowing what needs to be built, what can be thrown away, and what deserves care, continuity, and quality.

Not every problem needs a robust system. Not every tool should live beyond its moment.

What actually gets democratised

Software development is becoming more democratic. Not because coding no longer matters, but because much of the handwork no longer determines who gets to participate.

It is now relatively easy to spin something up. To test an idea. To build a situational tool and discard it again. Software starts to behave more like a medium than a monument.

At the same time, this does not remove the hard parts. Vision still matters. Knowing what to build, for whom, and why does not get automated away. Nor does the work of building systems that are robust, scalable, secure, and efficient.

If anything, that work becomes more valuable.

Good developers do not become less important here. They become more important. Not because they type faster, but because they understand structure, trade-offs, and long-term consequences. The same goes for people who know how to deploy systems into production, test them properly, and keep them running once they stop being experiments.

What changes is the division of labour. A large amount of manual work has quietly been absorbed by tools. That opens space for non-coders to explore, and for coders to focus on what actually requires judgement.

So when people say “you no longer need coders”, they are pointing at the wrong thing. What is disappearing is not the craft, but the gatekeeping.

And in a noisier, more abundant landscape, that kind of discernment becomes the real advantage.