Passports, Phones, and the Future of Identity

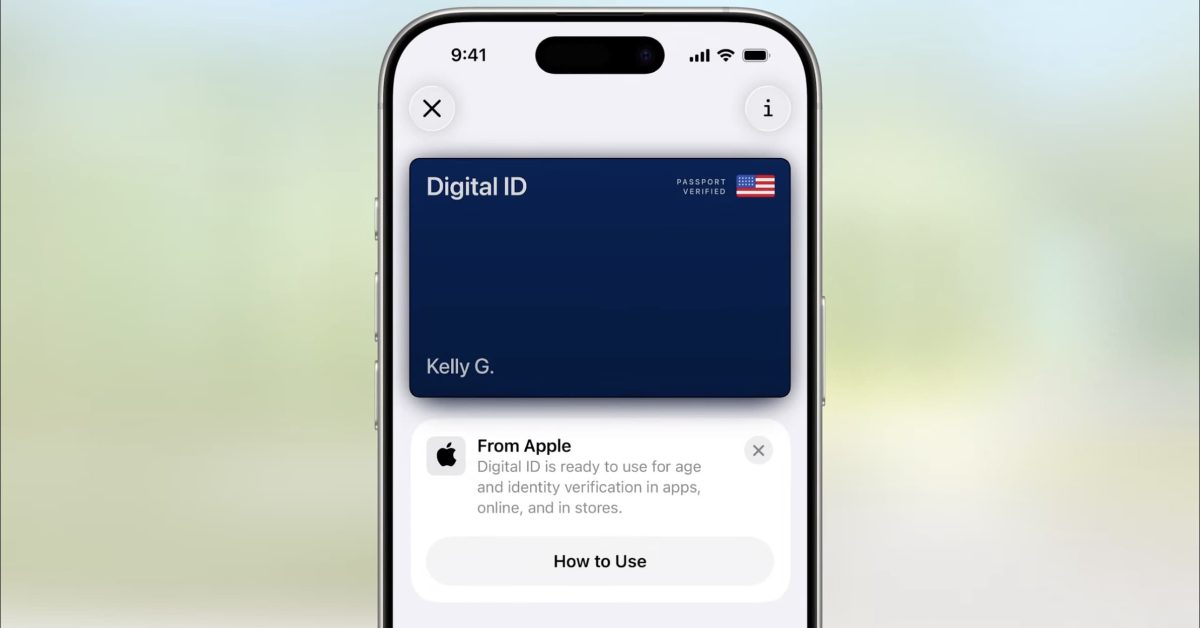

Apple adds digital passports to Wallet—but this signals more than convenience. It blurs the line between what we carry and how we’re identified online.

Apple’s move to support digital passports signals more than a technical update. It points to a deeper shift in how we carry, verify, and present our identity—increasingly through our phones. What happens when these familiar devices become both a bridge and a bottleneck to access?

From Plastic to Pixels

Apple Wallet’s upcoming support for government-issued identity documents, including the US passport, might appear to be a natural convenience: placing your ID alongside your boarding passes and bank cards.

But beneath this seamless integration lies a deeper convergence—between the digitisation of physical documents and the centralisation of online identity authentication.

Two Currents Converging

These are two distinct developments. A digital version of your passport, driver’s licence or ID card is a format shift—a way to carry the same information in your pocket, enhanced with biometrics and cryptographic protection. It is, in principle, still rooted in the physical world. You can lose your phone, renew your passport, show it at the border.

Online identity, however, is another construct entirely. It encompasses your logins, profiles, and presence across digital platforms. Increasingly, this online identity is being linked back to government-issued credentials. This is most evident in areas such as banking, healthcare, and platform moderation.

In Europe, this development is shaped by eIDAS, the EU framework for interoperable digital identities. Meanwhile, Big Tech’s identity systems continue to function as de facto passports to vast parts of the internet.

Lessons from Abroad

The merging of these two spheres—physical identity made digital and online identity made official—is already a reality in countries like China. There, a single national identity enables access to both public and digital services.

This model offers efficiency, but it also introduces a logic of central oversight. If identity becomes programmable and centrally issued, it can also be revoked. A kill switch for your digital existence.

What’s at Stake

This direction raises questions worth asking:

- Who holds the authority to issue, verify, or withdraw identity?

- Can digital identity remain decentralised or plural?

- What happens if your credentials are denied or suspended?

There are, of course, practical advantages. Carrying your passport on your phone may reduce friction when travelling or accessing services. But the line between digital convenience and infrastructural dependency is vanishingly thin.

Once your phone becomes your passport, your wallet, and your login to everything else, losing access is no longer a minor nuisance, it is a fundamental rupture.

A Call for Reflection

We’re not there yet, but the direction is set. The future of identity is not just digital—it is increasingly programmable, conditional, and centralised. That shift deserves not just technical scrutiny, but civic reflection.