Everyday life runs on daily data

Mobile data, roaming and fibre form one system. We only start to notice it when circumstances change.

I almost never exceed 10 or 12 gigabytes of mobile data per month.

Not because I am particularly careful, or because I avoid my phone. It is simply how I use it. Messaging, email, maps, reading, some browsing. No music streaming, hardly any video. And whenever there is Wi-Fi, my phone switches over without me thinking about it.

For a long time, I assumed this made me an exception. It turns out it does not.

Recent Dutch figures suggest that mobile data use sits at roughly 10 to 11 gigabytes per SIM per month. That is not a niche. It is the middle. Many people use less, a smaller group uses far more, and almost all of that difference comes down to one thing.

Video.

An hour of HD video can easily consume three gigabytes. Do that a few times a week and you move far beyond the average. Not gradually, but abruptly.

What is interesting is that this does not happen automatically. For many people, mobile remains a lightweight layer. It is where you coordinate, check, skim, respond. The heavier consumption happens elsewhere, on fixed connections that are so present we barely notice them.

Fixed internet does the heavy lifting

At home, fixed internet usage in the Netherlands typically sits between 300 and 500 gigabytes per household per month, and often more. Streaming, updates, cloud backups, video calls, gaming. Increasingly AI-driven services as well.

Put next to each other, the contrast is stark. Fixed connections carry roughly thirty times more data than mobile connections do, per subscription. Not because mobile networks are underused, but because they are not built for sustained bulk traffic at that scale.

This is structural, not temporary.

Mobile operates over shared spectrum. Capacity is finite, local, and collective. Fibre scales differently. Once it is in the ground, adding traffic is mostly a matter of equipment, not physics.

This is also why “unlimited” mobile plans always come with conditions, and why roaming limits persist, even within Europe. The language suggests abundance. The infrastructure quietly enforces boundaries.

Roaming as a reality check

Those boundaries become visible when you travel.

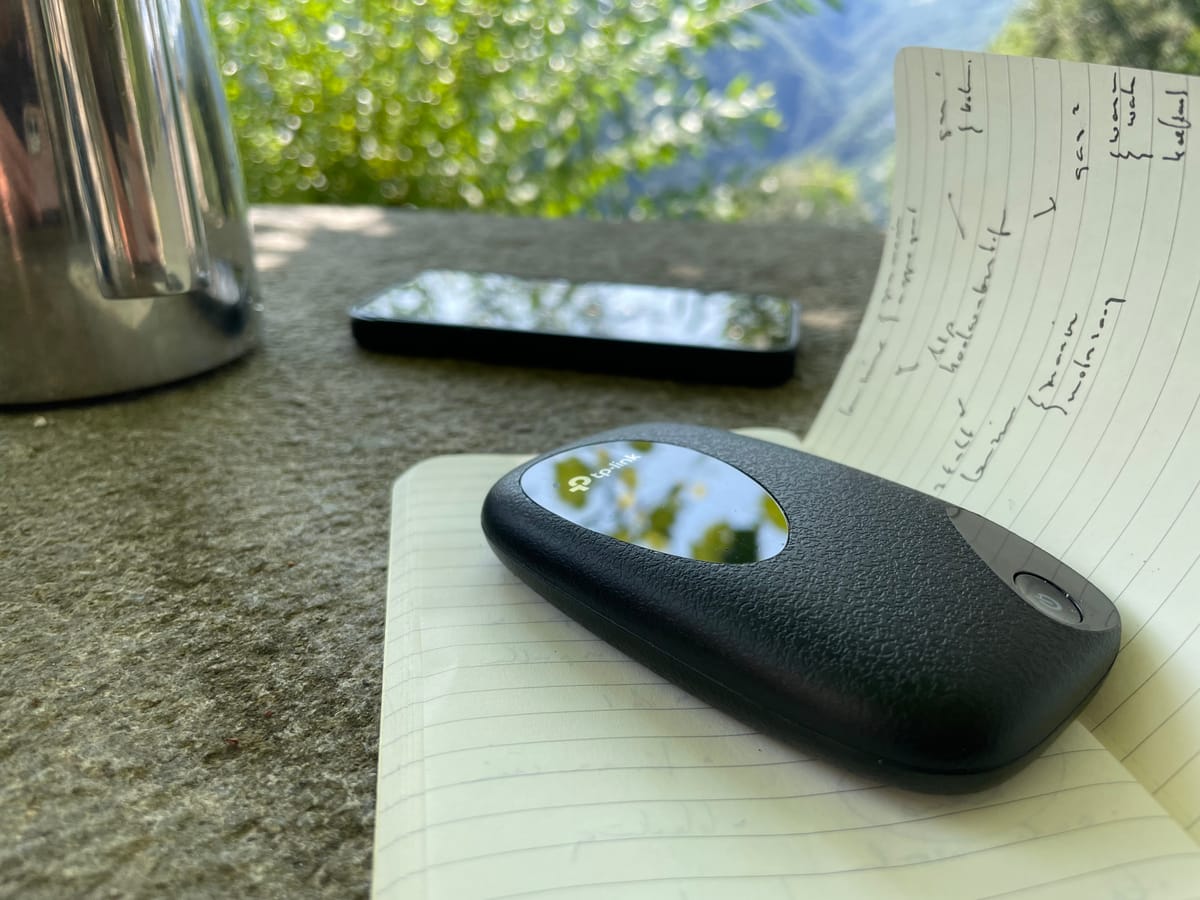

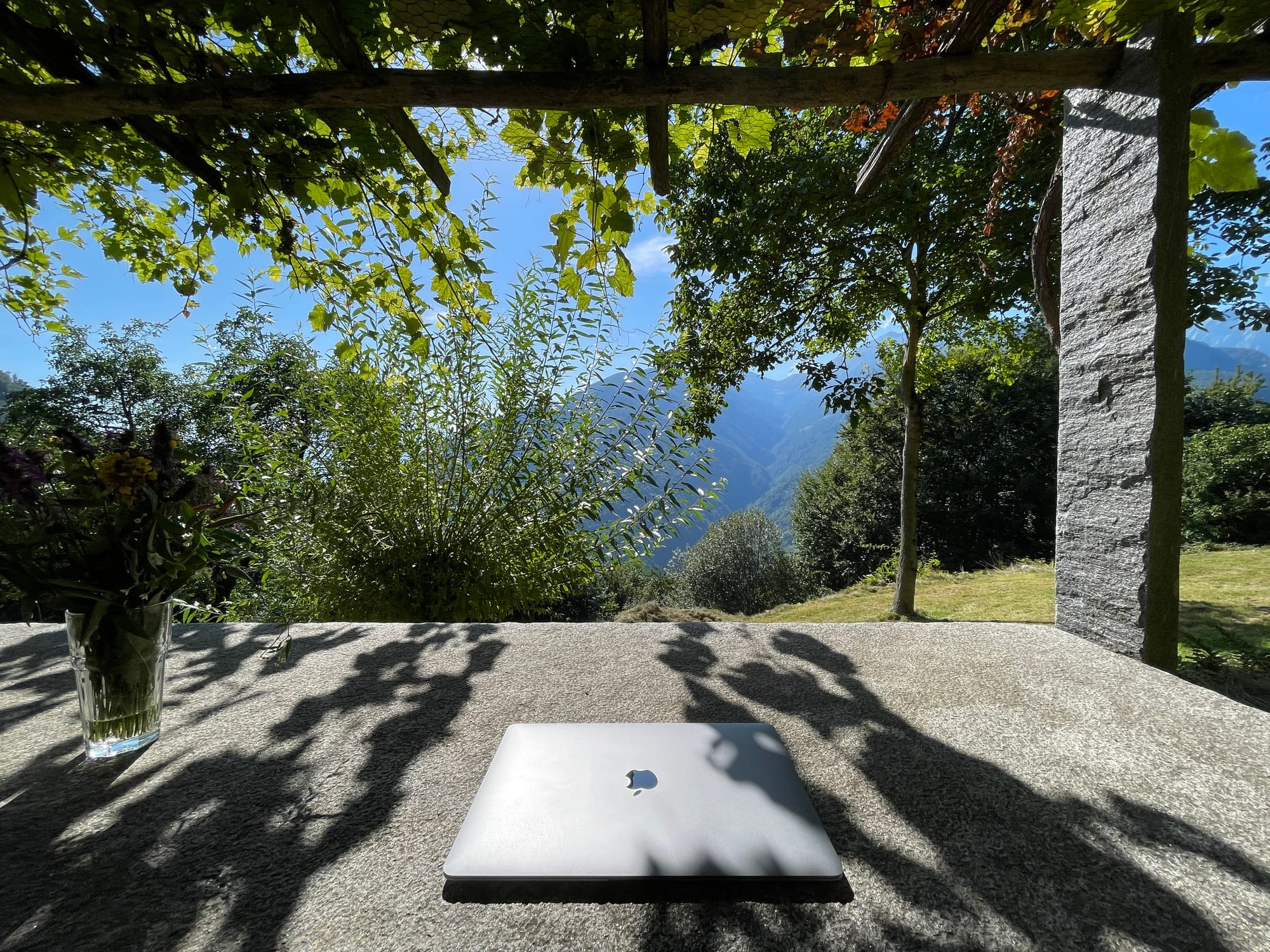

I often spend holidays in places that are genuinely off-grid. No cable. No fibre. Sometimes no Wi-Fi at all. And although it is a holiday, it can also be a working week.

That is when mobile stops being a complement and becomes the backbone.

On paper, everything looked fine. My roaming plan said “unlimited”. In practice, I ran into limits almost immediately. After about one gigabyte of use, speeds dropped to the point where video calls or sustained work became difficult.

Nothing was broken. This was the plan working exactly as designed.

“Unlimited” did not mean unconstrained. It meant continuous access, with an assumed usage pattern.

What “unlimited” actually means

Across domestic mobile plans, EU roaming, and travel eSIMs, the logic is consistent.

Unlimited protects you from:

- hard cut-offs

- surprise charges

It does not protect you from:

- capacity limits

- congestion

- fair use thresholds

Especially for roaming and travel eSIMs, “unlimited Europe” almost always means unlimited access, not unlimited throughput. There is usually a daily or monthly full-speed allowance. After that, you are still connected, but on different terms.

This works well as long as mobile remains secondary. The moment it has to replace fixed internet, the limits surface.

Holidays as stress tests

Holidays make this visible.

Fixed Wi-Fi disappears. Mobile usage spikes. Not because behaviour suddenly becomes extreme, but because context changes. Mobile absorbs traffic that would normally land on fibre.

Limits appear. Expectations adjust. Video quality drops. Offline modes suddenly make sense again.

What this shows is not excess, but elasticity. We adapt quickly when constraints are felt.

One system, different roles

Mobile data, roaming, and fixed internet are often discussed separately. In practice, they form one system.

Fixed connections carry the bulk. Mobile provides continuity. Roaming exposes the seams. When one layer weakens, the others compensate, up to a point.

Total data usage keeps growing, but unevenly. It accumulates where the system can handle it most efficiently. Expectations follow, until they meet constraints and recalibrate.

Video is where that recalibration becomes unavoidable.

Knowing where you stand

None of this requires optimisation. But having a rough sense of your own data usage is a form of digital literacy.

Not to chase averages, but to understand what your habits rely on. How much of your digital life assumes fixed connectivity. And why “unlimited” so often turns out to be contextual rather than absolute.

I still rarely exceed my mobile allowance. Not because I should, but because it fits how the system actually works.

That, more than the headline numbers, is the pattern worth paying attention to.

Who uses mobile data, and how

To make this more concrete, the charts below show two complementary views: how mobile data is typically distributed across activities, and how mobile data use is distributed across users. They do not describe the Netherlands specifically, but reflect a pattern that shows up consistently across mature mobile markets. The key point is not the exact percentages, but the shape of the distribution: video dominates total mobile data volume, while a relatively small group of heavy users accounts for a disproportionate share of usage.

Mobile Data Usage by Category (typical distribution)

| Category | % of total mobile bytes |

|---|---|

| Video streaming | 60–80% |

| Social media | 8–15% |

| Web browsing | 5–10% |

| Audio streaming | 3–7% |

| Other/background | 2–5% |

Mobile Users by Data Consumption Bucket

| Users (%) | Monthly Data Used |

|---|---|

| ~40–50% | < 5 GB |

| ~25–30% | 5–20 GB |

| ~15–20% | 20–50 GB |

| ~5–10% | > 50 GB |

Sources / methodology note

These distributions are based on recurring findings from international network measurement and traffic analysis reports, including OpenSignal’s mobile experience reports and Sandvine’s Global Internet Phenomena reports. Both analyse aggregated, anonymised mobile network traffic across multiple countries and operators. While national regulators such as the ACM do not publish application-level breakdowns for the Netherlands, the overall pattern shown here is stable across comparable European markets and helps explain why averages, fair-use caps, and roaming limits behave the way they do.