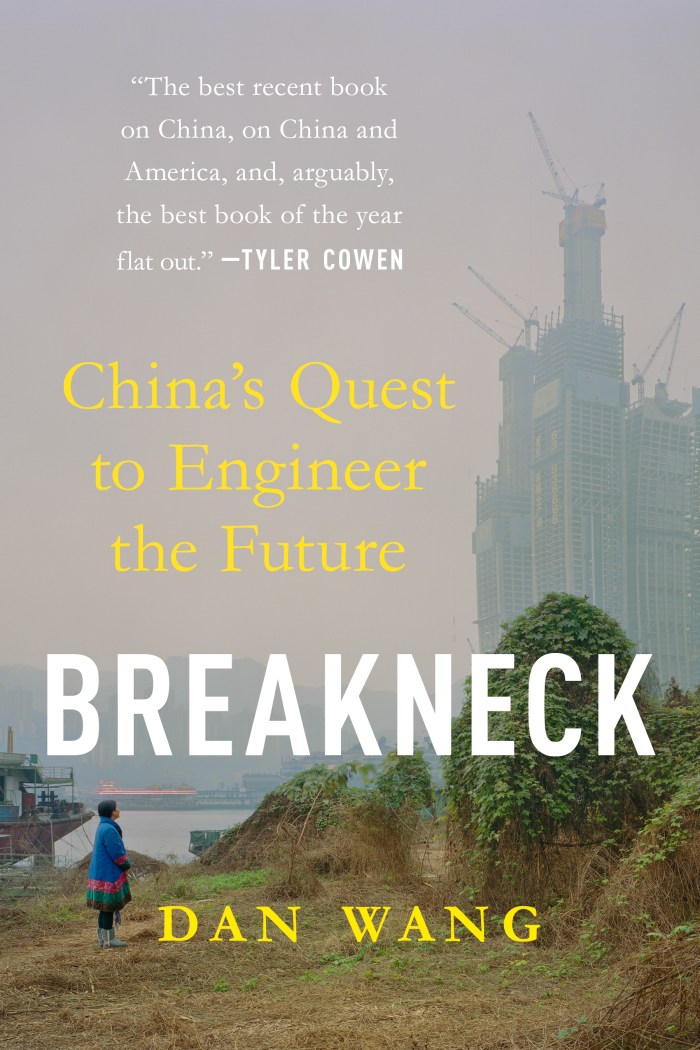

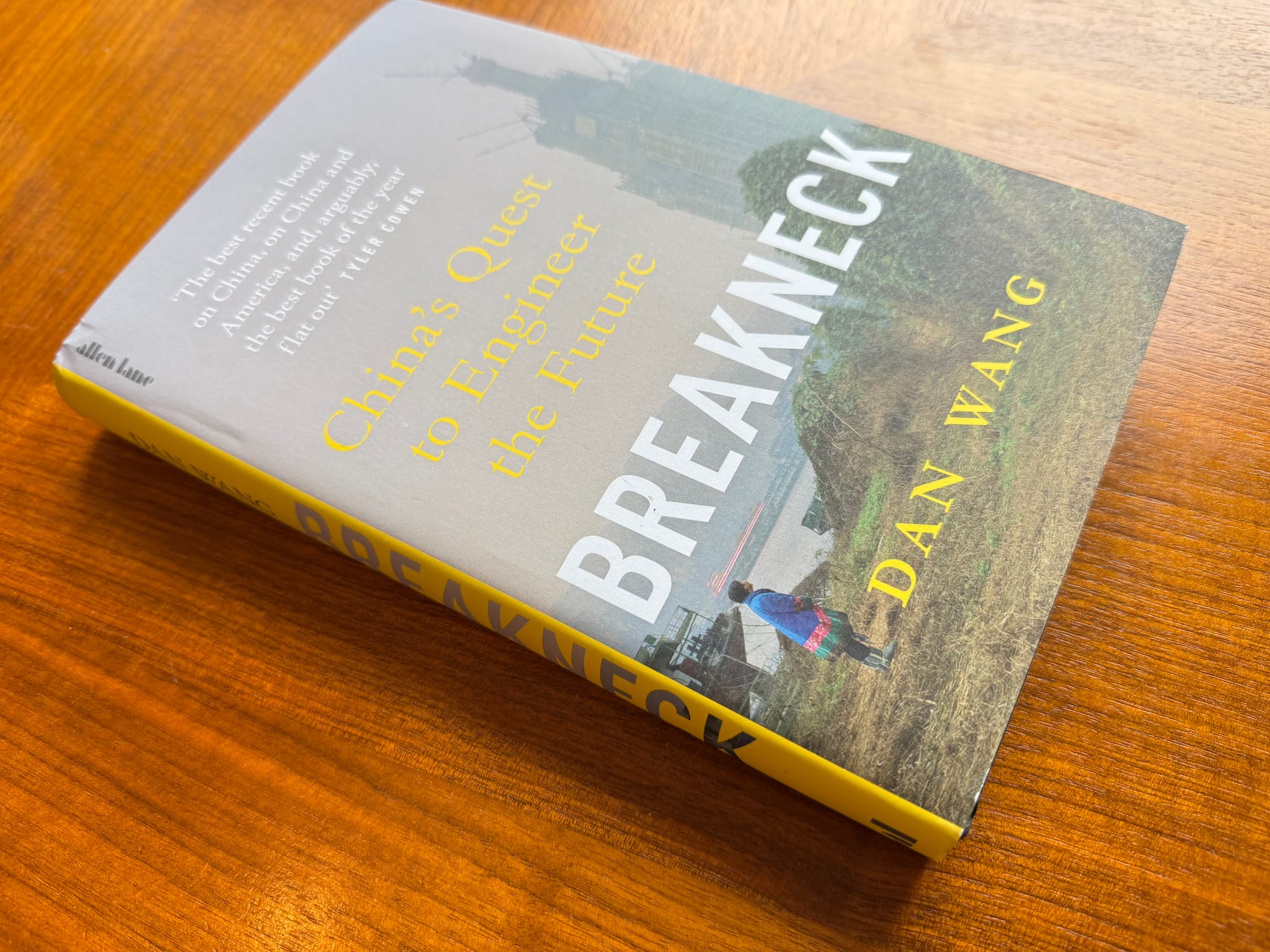

Reading Breakneck by Dan Wang

Few books capture our accelerating era like Dan Wang’s Breakneck: global, personal, and clear-eyed about what drives modern change.

Dan Wang’s Breakneck is the rare book that fuses lived experience, economic history, and cultural observation into one continuous argument. It is about China’s rise, but not only; it is also about America’s distance from what it once knew how to do.

Reading this compelling book, one feels the pull of two gravitational centres, China’s factories and America’s myths, orbiting the same system. The book doesn’t moralise. It simply shows how the world’s material and mental geographies have drifted apart, and how that divide explains much of what we are now living through: tariffs, supply chains, the quiet rearrangement of global confidence.

Quick takeaways

- Breakneck documents China’s transformation through the eyes of an observer who built his own life between China and the US.

- The book’s power lies in its blend of reportage and reflection: macroeconomics seen from the street level of factories and offices.

- It reveals the continuity between China and the US, less rivals than intertwined halves of one industrial civilisation.

- It suggests that the world’s current fractures are symptoms of a deeper split between the material and the mental.

- For Europe, the book is not a mirror but a question: where do we stand between these two ways of being modern?

Reflection

Making

What makes Wang convincing is not ideology but observation. He writes about engineers, toolmakers, and production lines with the familiarity of someone who has stood among them. Through these details, the abstract word growth regains texture. China’s development is not a theory; it is the rhythm of welders, logistics hubs, and 996 office routines.

“What do engineers like to do? Build. Since ancient times, the emperors have tried to tame the mighty rivers that sweep away not only farmland, but also imperial reigns.”

Designing

China’s devotion to engineering extends beyond machines to the design of society itself. The Party’s confidence in planning has produced not only bridges and railways but also engineered behaviours and beliefs.

Wang captures both the brilliance and the strangeness of that impulse: a conviction that any problem, moral, urban, or human, can be solved through design. It is a love of order that shades easily into control.

The result is a world that feels both inspiring and faintly inhuman, a place where progress risks becoming procedural.

“As the United States lost its enthusiasm for engineers, China embraced engineering in all its dimensions. Its leaders aren’t only civil or electrical engineers. They are, fundamentally, social engineers.”

Drifting

Across the Pacific, Wang finds a different energy: imaginative, individualistic, and increasingly detached from the material world. Silicon Valley builds platforms, not bridges. Its optimism runs on metaphors, not machines.

Wang doesn’t judge; he connects the two. America’s appetite for innovation found its outlet in China’s factories. The two economies, he writes, “co-evolved,” feeding on each other’s strengths and blind spots.

“Lawyers have so many tools available to delay or prevent building. You don’t just feel the difference going from the lawyerly society to the engineering state: you saunter, tread, and amble upon its works.”

He also introduces a term that crystallises America’s condition: Lawyrism. It describes a society so wrapped in legal reasoning that law becomes both weapon and refuge. What began as a means of protection now preserves hierarchy. Rules replace judgment; process replaces courage. In such a culture, progress stalls not for lack of talent but for fear of liability.

“While engineers envision bridges, lawyers envision procedures.”

Living

Beyond economics, Breakneck is also personal. Wang writes about his parents’ migration, about the quiet costs of mobility, and about China’s one-child generation with rare tenderness.

Those chapters changed how I thought about policy: not as demographic management, but as biography written by the state. They remind the reader that statistics have private echoes and that modernisation rearranges families as much as factories.

“The one-child policy is one of the searing indictments of the engineering state. It represents what can go wrong when a country views members of its population as aggregates that can be manipulated rather than individuals who have desires, goals, or rights.”

“In moving to the West, my parents made a wrenching personal decision based on what amounted to a guess about the future… All these years later, it’s not an open-and-shut case that they made the right call.”

Looking from Europe

Reading this, I often paused to locate myself as a European. The book speaks fluently of two civilisations that define the global century, yet Europe appears mainly as context, sometimes admirable, often cautious. Our respect for engineers has waned, but perhaps less than in the US.

“Europeans have a sense of optimism only about the past, stuck in their mausoleum economy because they are too sniffy to embrace American or Chinese practices.”

We still build wind turbines, EUV machines, and tunnels, but rarely mythologise them. Wang’s contrast made me see that omission more clearly: we speak about regulation, not production; about ethics, not execution.

His Europe is more museum than workshop, competent, sceptical, self-aware, a civilisation that prefers refinement to reinvention. It is an unflattering image, yet a useful one. It shows what happens when the moral energy of law and restraint is no longer matched by the physical energy of making.

The tension Wang traces, between the tangible and the abstract, is no longer academic. Tariffs, semiconductor bans, data laws are all manifestations of a deeper unease about who controls the world’s physical base. The digital layer may seem dominant, but without the material layer it floats, weightless. Breakneck restores that weight.

For a European reader, the book is not about imitation but perspective. It reminds us that progress is made of matter as well as meaning, and that ideas lose their force when they are no longer embodied in things.

Closing

Breakneck is, above all, an act of witnessing. Of someone standing in the workshop of history and noticing how the tools have changed hands. Wang’s prose moves between admiration and melancholy, precision and empathy. The result is a map of how the modern world actually operates, beneath its slogans.

“I like to imagine how much better the world would be if both superpowers could adopt a few of the pathologies of the other… I don’t want to get rid of lawyers. Rather, I want to help lift the engineers back up.”

For me, the book reawakened an older intuition: that civilisation depends on balance between thought and manufacture, freedom and form.

China and the US represent two extremes of that duality. Europe, if it still has a role, might be to remember how to hold them together.

And most, I recommend the book, I am sure you will learn something from it while enjoying the read.