Why WhatsApp Channels Trigger the Digital Services Act

WhatsApp did not become social media overnight. But Channels added public reach at EU scale. That single design shift is enough to activate the logic of the Digital Services Act.

For a long time, WhatsApp felt easy to place. It was a communication tool: private, conversational, and largely absent from debates about platforms and media. When doubts arose, they tended to focus on groups and communities. Is WhatsApp still “just messaging”, or has it become a form of social media?

A poll I ran some time ago reflected that ambiguity. Roughly half of respondents saw WhatsApp as a communication tool; the other half as a social platform. What almost no one mentioned was a third role that, in hindsight, turns out to matter most.

WhatsApp has also become something people read.

From private exchange to public reach

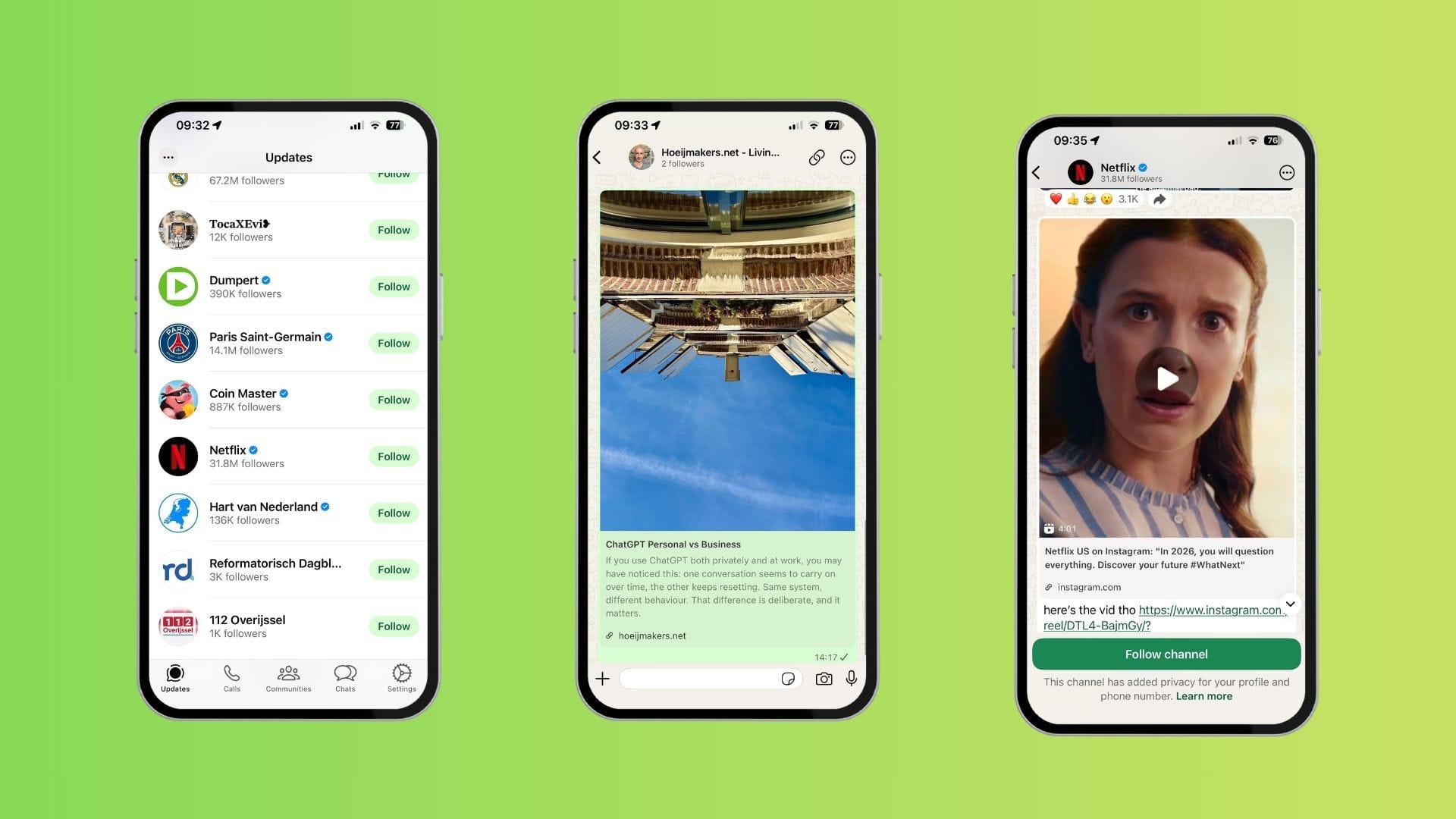

With the introduction of Channels, WhatsApp added a layer that sits alongside private chats and groups, but behaves very differently. Channels are one-to-many by design. They are asymmetric. No shared conversation is required. Updates flow outward and are often consumed passively.

This matters not because Channels resemble broadcasting in a cultural sense, but because they introduce public reach. Information is no longer exchanged between known participants. It is distributed to an open or semi-open audience, defined by interest rather than relationship.

That single shift is enough to move a service into a different regulatory category.

How the Digital Services Act sees platforms

The Digital Services Act does not regulate platforms based on how they are branded, nor on whether they feel like media. It regulates based on whether a service structures public reach at societal scale.

This is why services as different as app stores, maps, marketplaces, and video platforms can all qualify as Very Large Online Platforms. What they share is not content type, but function: they intermediate access, visibility, or distribution for a broad public.

Crucially, the Act applies at service level, not company level. Ownership alone is not decisive. Different services operated by the same company can fall under different obligations if their function and reach differ.

Core WhatsApp messaging remains private, enclosed, and non-discoverable. It does not shape public attention, even at enormous scale.

Channels do.

Why scale alone is not enough

This also explains why WhatsApp messaging itself is not treated as a Very Large Online Platform. Size is necessary, but not sufficient. Private communication, even when widely used, lacks public reach. There is no general audience, no system-level visibility, and no platform-level structuring of attention.

The Digital Services Act is explicit about this boundary. It is not a law about communication. It is a law about public intermediaries.

Channels cross that boundary by design.

The quiet irony

The irony is not that WhatsApp is now being examined under the Act. The irony is that this happened without a dramatic product shift. Channels felt incremental, almost modest. And yet they introduced exactly the condition the law is designed to notice: outward-facing distribution at population scale.

At the time of writing, WhatsApp Channels have crossed the relevant user threshold, but no formal designation decision has yet been issued. Nothing has gone wrong. No judgement has been made. This is simply the law doing its work as intended: observing scale, then assessing responsibility.

Why this example matters

As an illustration of European digital legislation, this case is unusually clean. It shows that the Digital Services Act does not ask platforms what they are, but what they enable, once enough people rely on them.

Platform identity, in this framework, is not a matter of self-description.

It is inferred from public reach.

And sometimes, that inference reveals that a messaging app has become something else.

-> Whatsapp channel for this blog

Current designated Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) under the DSA

(service-level designation; illustrative, not exhaustive)

- AliExpress

- Amazon Store

- Apple App Store

- Booking.com

- Google Play

- Google Maps

- Google Shopping

- Snapchat

- TikTok

- X

- Wikipedia

- YouTube

- Zalando

Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs)

1. Google Search

2. Bing