The Persistence of the Table

Beyond structure and data, a table is a surface where accumulation becomes glimpseable and time, for a moment, held still and open to inspection.

Things keep happening.

Events accumulate. Transactions, measurements, messages, decisions, states. Time does not just pass; it leaves residue. And once there is residue, there is a need to hold it, inspect it, and make sense of it without having to relive it.

One of the oldest and most reliable ways we do this is by putting time into rows.

Time made inspectable

A table does something deceptively simple.

It takes succession and turns it into adjacency. What happened earlier and what happened later are no longer separated by time, but placed next to each other in space. Events become rows. Time becomes order.

This move is so familiar that it often goes unnoticed. But it is foundational.

Without it, accumulation would remain narrative. You would have to move through time again and again to understand what has happened. With it, time can be paused, flattened, and held in view.

A table is not primarily about data. It is about making progress inspectable.

Accumulation needs a surface

As soon as things accumulate, a surface becomes necessary.

Ledgers, logs, registers, inventories, timetables. Across history, tables appear wherever continuity matters. Not to tell stories, but to allow comparison. To see what is growing, repeating, deviating.

What matters is not that the information is structured, but that it is laid out. Laid out so it can be seen all at once, or at least in parts, without traversing the whole sequence again.

This is why tables feel less like documents and more like workspaces. They are places where time has been temporarily stabilised.

Glanceability as a human response

Once time has been spatialised, a particular human mode becomes possible: glancing.

Glancing is often treated as superficial. In practice, it is how humans cope with accumulation. It allows orientation without immersion. Pattern recognition without commitment. A sense of “enough” without completion.

Tables support this unusually well. You can skim, pause, return. You can look briefly and still learn something reliable. You do not have to resolve meaning to extract signal.

In this sense, glanceability is not a design feature. It is the human complement to temporal compression.

Why tables keep resurfacing in software

Much of modern software deals with accumulation. More data, more events, more state over time.

Interfaces change. Visualisations come and go. But when understanding becomes difficult, systems tend to expose a table. An admin view. An export. A debug panel. A list of rows ordered by time.

This is not a failure of imagination. It is a return to a form that reliably turns ongoing process into something that can be inspected.

Spreadsheets and databases sit on opposite sides of this tendency, but share the same core move. Both are ways of holding accumulated time in a stable, glanceable form. They differ in governance and scale, not in essence.

Feeds as disguised tables

This becomes especially visible when looking at social media feeds.

A feed feels like flow. Like presence. Like “now”. But structurally, it is a table.

Each post is a row. Time is the primary ordering key. Metadata forms hidden columns. Filtering, ranking, and pagination are continuous table operations.

The experience of “keeping up” does not come from reading everything. It comes from being able to glance at accumulated time and decide that nothing essential was missed.

What looks like narrative immediacy is already ledger logic.

Machines and linear time

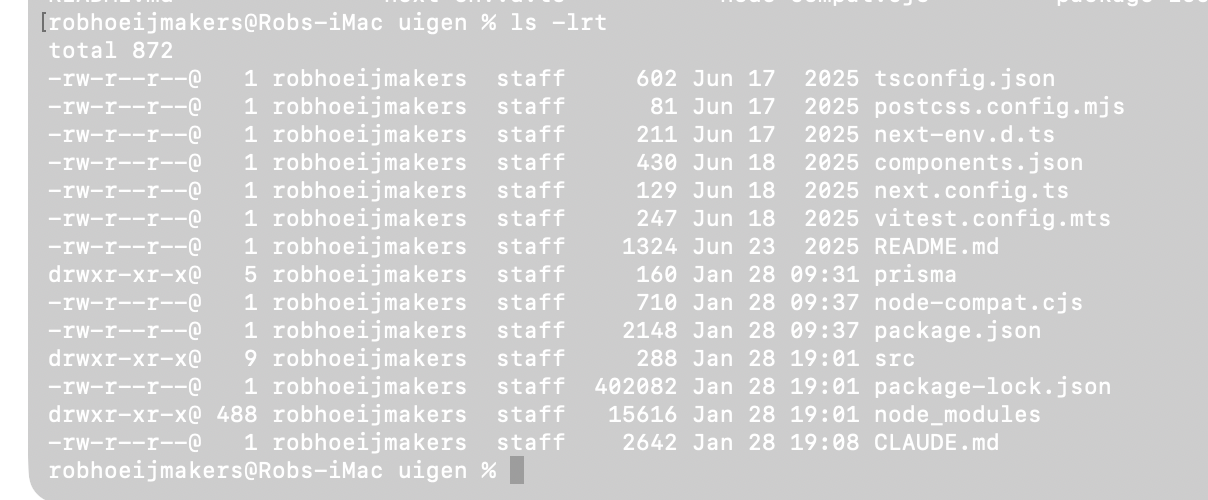

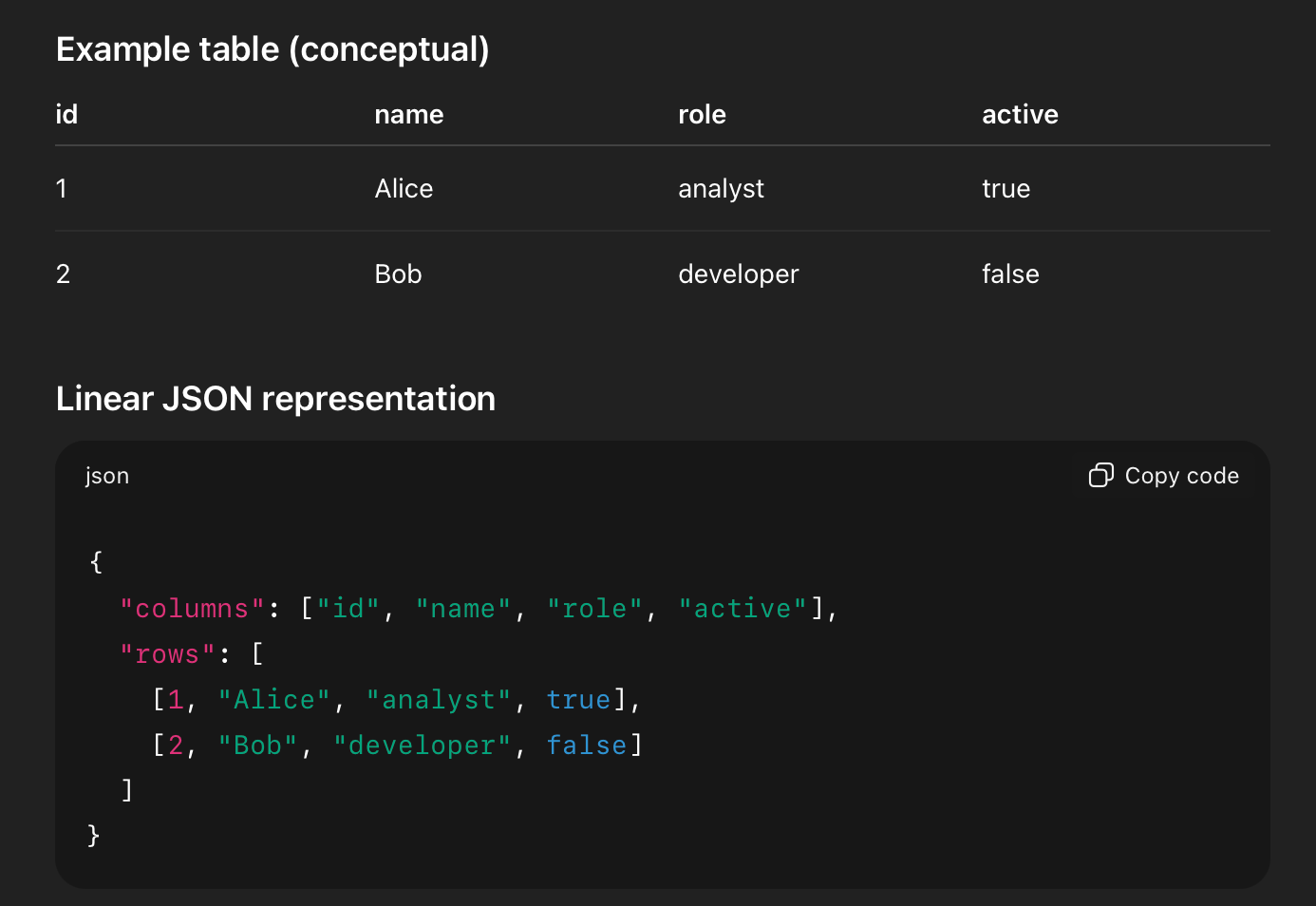

Large language models sharpen this contrast.

They read linearly. When they encounter tables, they do not perceive a surface. They process sequences. JSON, YAML, CSV are not spatial to them. They are linear encodings of structure.

What is glanceable to a human must be traversed again by a machine.

This does not diminish either side. It clarifies roles. Tables are not primarily for machines. They are for humans who need to hold time still long enough to think.

Something that does not go away

Software will keep changing. Interfaces will evolve. Data volumes will grow.

But as long as events accumulate, there will be a need to turn time into space. And as long as humans remain bounded in attention, that space will need to be glanceable.

That is why tables persist.

Not as a legacy form, but as a recurring answer to a permanent problem. How to live with accumulation without being overwhelmed by it.

For now, this is simply something worth noticing. Not a conclusion, but a grounding. A reminder that amid constant change, some forms endure because the pressures they respond to endure as well.