Reskilling the Mind: Europe’s Next Transition

No one truly knows what lies ahead. We can sense that work is changing, that the ground beneath knowledge and skill is moving, but the direction is still uncertain. This article is an exploration, a way to think aloud about what reskilling could mean for Europe when intelligence, both human and art

The premise

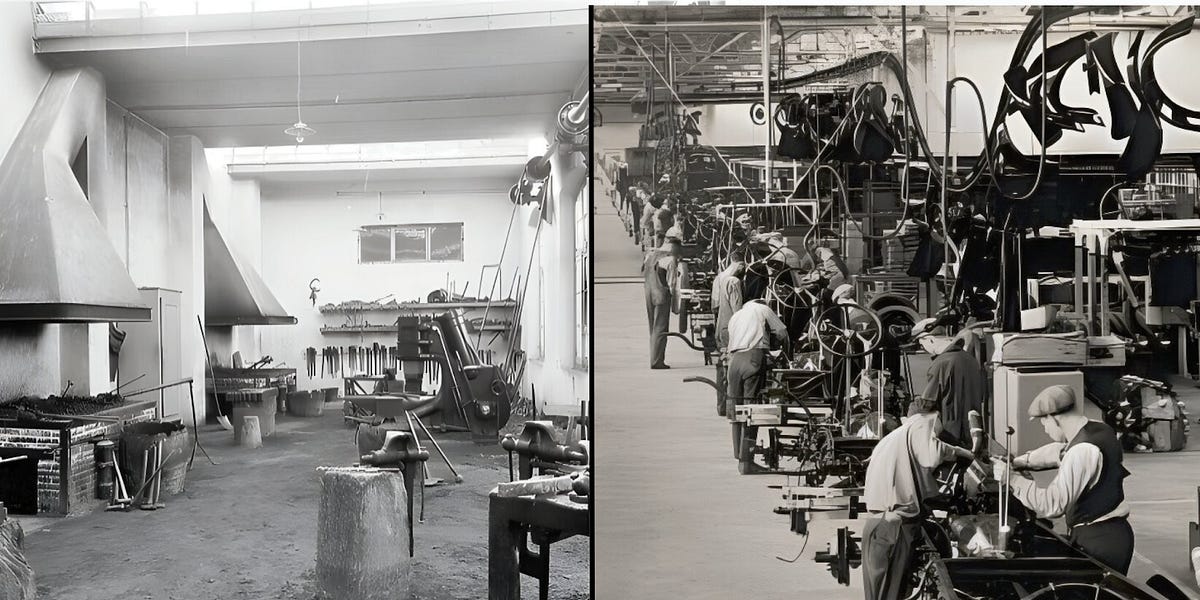

For half a century, Europe’s transformation has been cognitive. We traded the factory floor for the meeting room, the lathe for the laptop. Productivity became language-driven: managing, advising, interpreting.

Now that foundation is shaking. Artificial intelligence begins to do the very things that once made our economies “advanced.” The question is no longer whether we must reskill, but whether we can redirect our collective intelligence, and our industrial capacity, before the gap widens.

Looking backward

Every great transition has demanded a new kind of worker.

- The industrial turn pulled rural Europe into foundries and rail yards.

- The post-war reconstruction built technical and bureaucratic skill at national scale.

- The digital turn globalised services and thinned the material base of production.

What we face now is unusual: the thinking layer of work is under pressure, just as the geopolitical layer thickens again.

The new geography of work

Reskilling is not only cognitive, it is territorial. The return of power politics, supply-chain insecurity, and military re-armament forces Europe to reconsider what it means to be productive.

Defence, energy, and advanced manufacturing will require engineers, machinists, logistics planners, and technicians, people who can build again, not only advise or analyse.

In that sense, reskilling may also mean re-industrialising: reconnecting human skill to material capability. Europe’s long outsourcing of production has left it intellectually rich but strategically thin. Rebuilding competence in physical domains is as urgent as training people for digital fluency.

The civic dimension

Europe’s instinct is often to regulate what it fears. But legislation cannot replace lost skill. What we need is a continental project of learning and making, education as industrial policy, apprenticeship as security strategy.

Reskilling, in this view, is not a reaction to automation but an act of self-definition. It is how a civilisation decides what it still wants to know how to do.

Who will organise it?

In previous eras, reskilling was almost automatic because authority and direction were clear. Industrialisation had the factory. Reconstruction had the state. Digitisation had the corporation.

Today, none of these actors alone can carry the weight.

Governments can set incentives but move slowly and fear backlash.

Corporations train for narrow advantage, not for civic resilience.

Educational systems still treat knowledge as a stock to be transmitted, not as a capacity to adapt.

That leaves a vacuum, and perhaps a choice. Either reskilling becomes a managed transition, coordinated across states, sectors, and citizens, or it unfolds through disruption: job collapse, social anger, and reactionary politics.

Europe has historically preferred negotiated change over violent rupture. Yet negotiation requires shared purpose, precisely what decades of outsourcing and fragmentation have eroded. The challenge is not only to train people, but to rebuild trust between the institutions that would have to act together.

Reskilling as sovereignty

If knowledge work is no longer Europe’s safe harbour, what becomes the new basis of dignity and contribution? Perhaps the next social contract lies somewhere between code and craft, between intelligence and manufacture, a re-balancing of mind and matter.

Reskilling, then, is not only about adapting to AI. It is about re-establishing sovereignty: cognitive, industrial, and human.